This is the second in a series of guest blogs by the 2025-26 Michigan Regional Teachers of the Year. Thomas Schultz is a science teacher at Charlevoix Middle/High School in Charlevoix Public Schools.

As Michigan’s Region 2 Teacher of the Year, I often think about what it really means to teach students not only about science, which is my content focus, but about other skills and virtues.

At Charlevoix Middle High School, I teach high school Forensic Science and Honors Chemistry, and one section of seventh-grade science. Over the years, I’ve seen students come into class carrying all sorts of anxiety and doubt about what they can accomplish. Many arrive already convinced they aren’t “math people” or that “science just isn’t their thing.” Sometimes these ideas even come from well-meaning parents who want to explain away a struggle. But when students believe they can’t, they rarely get the chance to discover that they, in fact, can.

Over my 25 years in education, I have found that rigor isn’t the enemy, it’s the path to growth. If we lower the bar, we deny students the satisfaction that comes from working hard and figuring things out for themselves. And let’s be honest: Rigor doesn’t have to be joyless. It just must be meaningful. Students should leave the classroom feeling like they’ve wrestled with a problem, not just filled in a worksheet or jumped through proverbial hoops in vain, learning nothing.

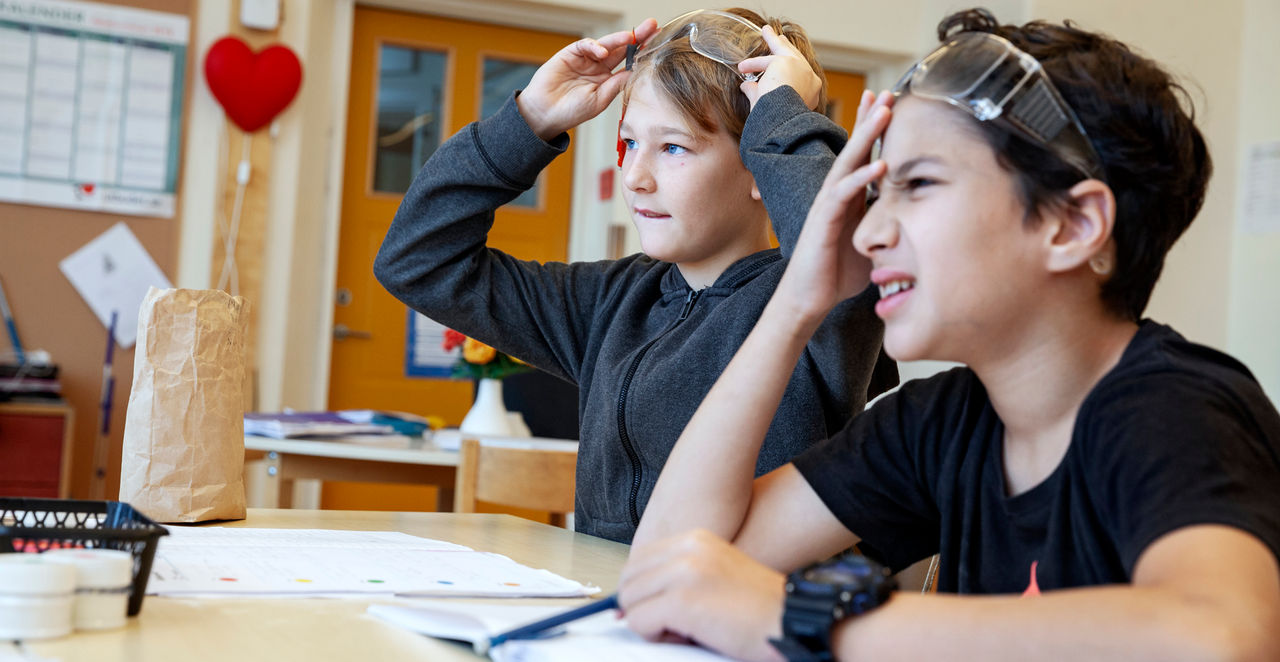

One of my favorite examples comes from my Honors Chemistry class. When we study density, students aren’t just given formulas – they design a “submarine” using a film canister with a hole in the lid. The challenge: Make it sink to the bottom of a 1,000-milliliter graduated cylinder, stay down as long as possible, and then come back up. They work in pairs, testing and retesting, adjusting their designs and figuring things out on their own. We even have a little competition to see whose submarine stays down the longest. It’s messy, frustrating at times and fun all at once.

And by the end, students aren’t just learning about density – they are learning they can do hard things. They are learning that success isn’t instant, and that failure is oftentimes the best teacher. A lab scenario like this allows students to acquire small wins, moments that were just outside their reach… but within their grasp. These small successes keep them coming back as they taste the fruit of those successes. This is how you build good habits, resilience and stamina.

Beyond the classroom, I’ve loved organizing Family Science Nights, where my high school students become the teachers for elementary students and their parents. Armed with Van de Graaff generators and other hands-on demonstrations, they guide younger learners through experiments that spark curiosity and excitement. These nights are a reminder that learning science is about more than facts – it’s about confidence, collaboration and discovery. As their teacher, I hear the explanations from my high school “Chemistrators” improve throughout the night as they build confidence in realizing how capable they are and how rewarding it is to teach others.

The same idea applies at home. Students need structure and examples of what it looks like to be disciplined. They need the chance to experience success after working hard. Parents and guardians play a key role here, too: It’s OK to be the parent/guardian, to say no when needed and to hold kids to high standards. Encouraging them to replace screen time with meaningful activities like helping around the house, assisting a neighbor or simply having a conversation without devices teaches responsibility, builds empathy and strengthens family connections.

These are the kinds of experiences that shape young people into adults who not only handle challenges but also value the virtues we admire in the people we look up to: resilience, integrity and perseverance.

Our job together as educators, parents/guardians and caregivers isn’t to remove obstacles for students, but to really walk beside them as they search for answers to who they are, what they can accomplish and how they can positively impact the lives of others. The earlier we help our students and children practice these skills, the more natural resilience and confidence become in shaping their future. When we are intentional about this, they learn a lesson that lasts a lifetime: They can do hard things, and doing them well is worth every effort.